When Breaking the UX Rules Makes Sense

If you are a UX designer, you do a lot of your work within the boundaries of design principles, common patterns, and best practices. All of these ‘rules’ exist to help you design the most efficient user experience. And this makes them helpful to some extent.

But UX rules are not set in stone, they change over time, impacted by trends in design and user behavior. This is why great designers view them only as guidelines and consider their specific context before making decisions.

Breaking the rules and making bold choices is what drives innovation - as long as you make them with your users in mind.

Test with users first

What will happen if you didn’t test your design with your users? No matter how current your design is and how well it follows best practices, there is a big chance that users won’t be happy with the final product.

You’ll use UX patterns that are likely to ensure some of the expected outcomes for the users, but that is rarely sufficient enough to deliver a truly great user experience.

On the other hand, UX testing will inevitably drive design change. It will give you ideas to experiment with and possibly inspire you to break some of the rules followed in your initial design to improve the overall user experience.

Quite often, test users design the product without even realizing it. When they are really relaxed about the whole process, more often than not they will start verbalizing their expectations or suggesting some interactions that are borderline SF.

The end result is usually a collection of ideas and concepts that might not be that common but might be interesting to test.

Don’t get fixated on your ideas - observe your users!

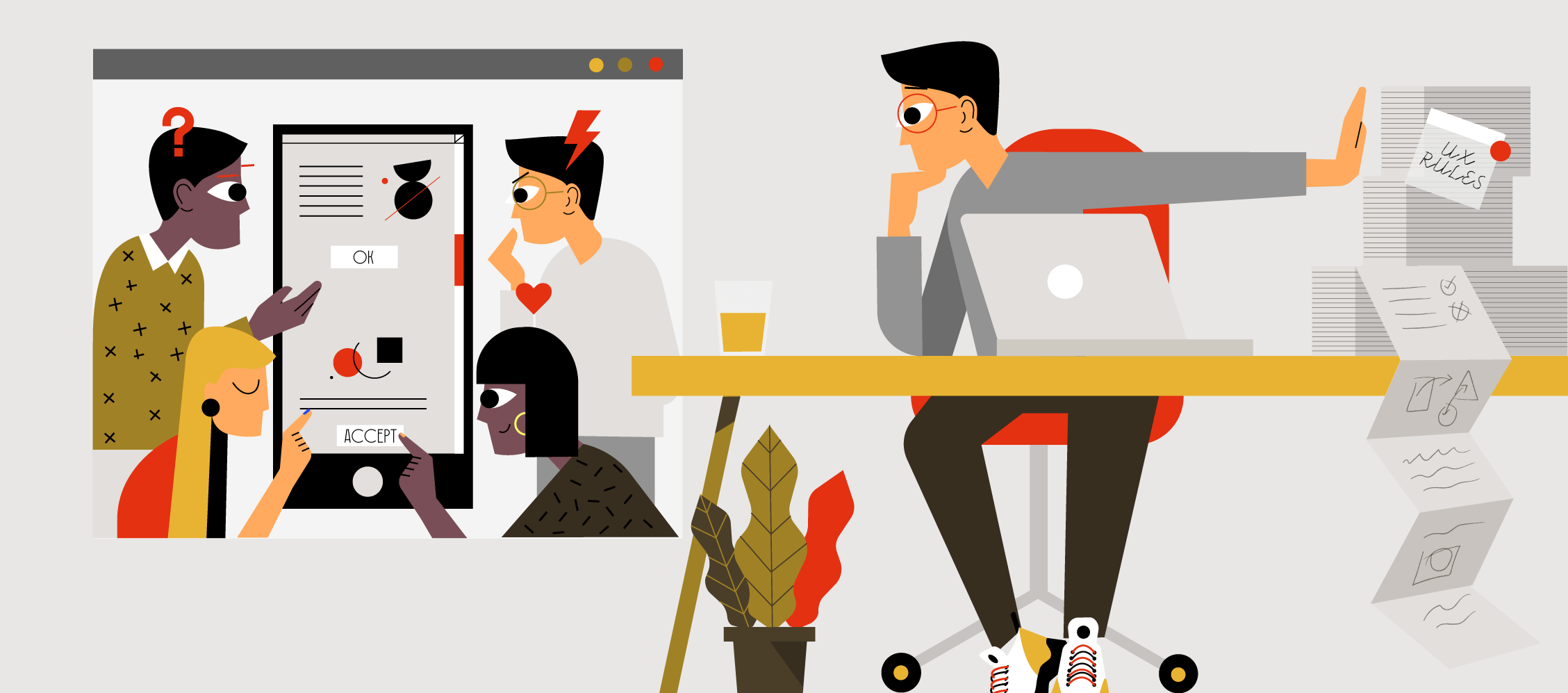

We’ve all seen this scenario - the product owner pushes her ideas about where the issues in a workflow may exist, the UX designer pushes his, and the most important viewpoint - that of the users - gets neglected.

Instead of falling in this trap, run in-person or remote usability tests that allow you to observe your users and ask them questions about their experience with the product. Because no matter how well you followed UX design rules, you’re bound to make mistakes that cause glitches in the user workflow.

Let’s take material design as an example. It is a beautiful design framework used throughout the Google ecosystem. However, prototype tests showed that input elements were particularly tricky for casual users that do not surf the web every day. It took them a while to realize that the element is interactive. What they were expecting was a bordered rectangle with a label above it. In other words, a “traditional” input field.

As seen in the above example, feedback from the end users will typically uncover the pain points that would otherwise remain hidden. Observing your users will show you if there are any rules you need to bend or break for a particular project.

Prototype early in the design process

If you want to understand how well you’ve built an information architecture for your product, there’s no better way to do it than prototyping.

Thanks to prototyping tools like Koncept, the path of going from wireframes to interactive prototypes is incredibly easy, and the payoff can be significant. Interactive prototypes give users greater context regarding how performing a task will feel in the final product and how intuitive the workflow actually is.

This will give you a chance to observe how they interact with the application so you can see which prompts lead to hesitation or confusion. And yes, this can happen even if your design is based on best practices.

After all, best practices should be used only as a guideline and not an out-of-the-box perfect solution to any design problem. For example, it has been concluded that users do indeed scroll.

However, for one of the tests that included test users from early 30s to late 40s it turned out that the majority of them didn’t even try to scroll but expected to find what they were looking for “above the fold”. Changes needed to be made to provide hints to users that there is more content under the hero section.

Conclusion

Everything changes constantly, and so does design. That change isn’t always for the better, which means that any new direction should be challenged, and users always asked for feedback. Testing and experimenting is how we learn new techniques, but we can rely on rules as a foundation.

It is designers’ responsibility to learn about their users’ preferences, to observe and iterate, as this is the only road to making great products.

Perhaps we can conclude that “best practices” do not exist. We have to settle with “good-enough practices”.